In 1990 something game-changing happened. Something that would begin a conversation that is still evolving today with the #MeToo and #TimesUp movements. A relatively small, very liberal college made a new policy about consent; by doing so, it took a stance and started a movement unlike anything the world had seen before. Antioch University created the first "affirmative consent" sexual misconduct policy. This was the beginning of affirmative consent in the public purview and almost immediately, public commentators - and even "Saturday Night Live" - took a swing at how ridiculous it seemed.

“Ask explicitly before having sex? Get permission to touch someone? State what you want do before doing it? How bizarre! How unromantic! How unrealistic.”

Few believed such a sentiment would ever catch on, either on college campuses or in mainstream society.

But things were changing. In 2011, a wave of awareness hit college campuses all over the United States, especially for institutions that had yet to meet the kinds of ideals and standards Antioch had brought forward in the '90s. That year, a letter was sent out from the Obama administration to over 7,000 colleges across the country. It challenged the standard proceedings in sexual assault cases under Title IX and advocated for victims to be believed. Because of this letter, and similar sentiments echoed in the Clery Act, colleges began providing policies, programming and resources to curb sexual misconduct. This included a new perspective on consent in all its forms, from stalking and harassment to sexual contact. These changes trickled down to the courts and showed up in state and federal legislation.

But where did Antioch, or the White House in 2011, even get the idea for affirmative consent? The history of this is a bit shrouded in secrecy. The reason for this is that it is believed that a majority of these conversations started in the kink community. In the '80s and '90s, as HIV became part of sexual awareness, more attention was brought to all forms of safety. Sex without full consent and awareness could not be deemed safe - physically or emotionally - something that was important to the leather and BDSM community.

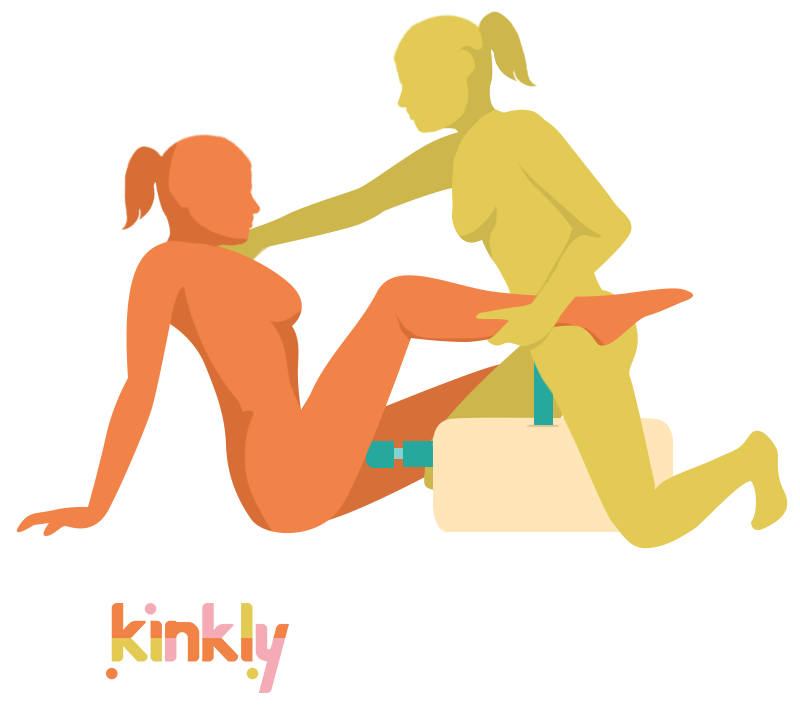

Kinksters already faced so many barriers and concerns for creating a viable community that they determined that violations of consent could not be tolerated. More and more kink groups wrote rules on asking permission and assuring that all participants at events were of sound mind and body to be making informed decisions. In 1981, a leather collective in New York, Gay Male S/M Activists (GMSMA), formed and created a community that would write the first consent bylaws. The concept of safe, sane and consensual was coined by GMSMA and used as a holistic discussion and benchmark for best practices around consent in kink play spaces. Today, the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom continues this mission with its Consent Counts program and resources. While history may never tell us for sure, there is a wide perception that the seeds of the consent movement were sown in the kink community and were what ultimately inspired the policy changes that were later seen on college campuses.

In 2018, consent and all of its complex attributes continue to spread. From #MeToo’s ability to shed light on what verbal and non-verbal consent means to an increased public outcry over high-profile cases such as Brock Turner’s appeal of “outercourse,” the momentum on challenging previous beliefs and standards and raising up victims' voices is snowballing at an incredible rate. In 2017, the state of California began to require that students across all grades receive education on consent as part of their health and sexuality curriculum. More and more books on puberty for adolescents are discussing bodily autonomy, and slowly parents are including these topics when they talk to their kids about sex.

So, are we on our way to eradicating sexual abuse and interpersonal violence? Is hope just there, right on the horizon? As a consent educator and sexual misconduct subject-matter expert, I am sad to say I think not.

So, are we on our way to eradicating sexual abuse and interpersonal violence? Is hope just there, right on the horizon? As a consent educator and sexual misconduct subject-matter expert, I am sad to say I think not. While society has made huge bounds and progressed in many ways, the flip-side is that we have wanted to make these changes so quick and easy that we have left behind some of the more challenging and most vital components.

Whenever I tell people that I’m a sexual misconduct consultant and sexologist the thing they most often say is, “Oh have you seen the “Tea and Consent” video? It’s so good.” Yes, I have seen it. In fact, I have used it myself - especially when talking to students with limited English language acquisition - as the illustrations help overcome some of those language barriers. But what I don’t get to say enough is that consent isn’t actually as simple as tea. I wish it were. It would make my job and life super easy and breezy, but this is just not the case.

Read: Why Consent Is More Complicated Than a Cup of Tea

As a community, we need to explore the complexities of culture, consent and where we want to go with this paradigm. In order to achieve a culture of consent, we must first unpack the cultures of rape that we ALL grew up with.

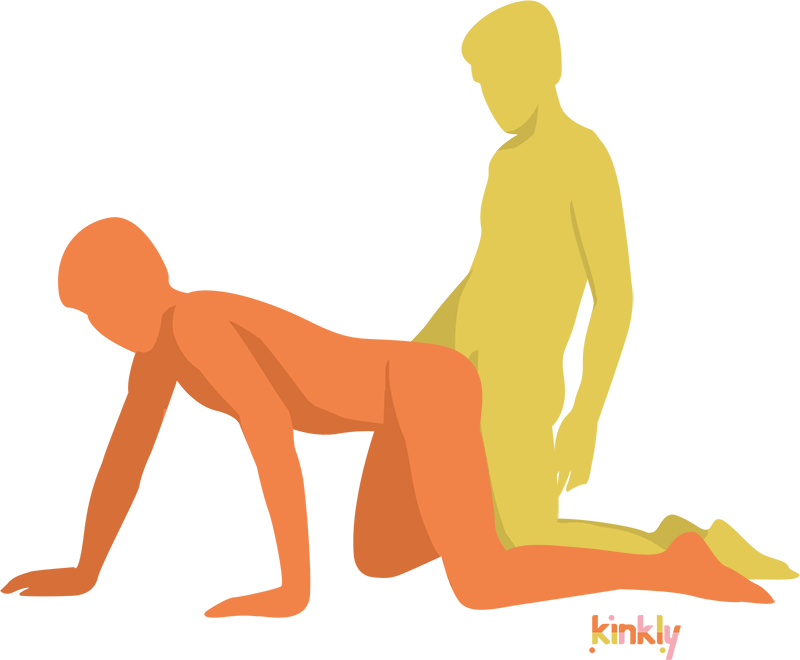

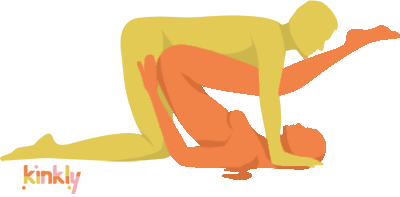

When we talk about sex as teens, we say things like “bumping uglies,” “tapping it,” “smashing,” and “tearing it up,” all of which invoke a sense that sex is dirty, inherently rough, and that good sex should always involve some sort of aggression and dominance. While, as the kink community would say, none of those things is inherently wrong or bad, they can be when taken out of context or when touted as the only way to be sexual.

Our movies, music and oral histories about sex tell us that consent is a second thought at best and a literal joke at worst. We often want to say that “no means no” should cover effective sexual assault prevention, but we fail to address the topic of token compliance (when a person is pressured to say yes) and token resistance (when a no is expected, so a person feels afraid to say yes). We avoid these intricacies because, well, they are tough. They don’t fit into a cute, catchy video or tagline, and they require a ton more effort, transparency and honesty. But here’s the good news: by having these hard and in-depth conversations we start healing the festering wound that is abuse and assault, instead of placing another band-aid on this hemorrhaging problem. So, let's get started.