Lgbtq

Disability and Sexuality: Desiring, Not Fetishizing

Disability and sexuality are not mutually exclusive. Ableist thinking, especially when it comes to sex, is demeaning to everyone.

What is sex? What is desire, desirability? For many people, the idea of sex and sex appeal rests on the cornerstone of physical strength and virility. A sexy body is powerful, long-lasting, and ready to go.

Great sex is physically intense, readily available, and reliant on genitals that respond properly. For anyone who can’t live up to these ideals, society thinks of them as undesirable or non-sexual, even childlike. If you can’t look and respond in the cookie-cutter way that the media and culture see sex, then are you even a real adult? A valuable person?

At the core of these issues is the topic of ableism. Ableism is the idea that bodies with disabilities are inferior to those without disabilities. There is a multitude of ways that this kind of thinking harms everyone.

From accessibility and physically navigating spaces to lack of resources such as education, housing, and healthcare the idea that people with disabilities are less worthy of every good and vital thing that life has to offer is one of the most pervasive and rarely discussed social ills.

In regards to sex and relationships, ableism feeds into two main narratives—that people with disabilities are either to be infantilized (seen as children and thus non-sexual) or fetishized (seen as an exotic sexual experience or the focus of dysmorphophilia) but almost never fully-fledged human beings.

Disability as a term is a broad and far-reaching umbrella concept that includes everything from people with chronic acute depression to those with visual impairment to folks with cognitive processing differences. Because of this, it is impossible to say that a certain experience is universal to all people in the disabled community but there are common threads of experience.

So how do we create conversations about including people of all abilities and are included in conversations and visions of desirability and sex without othering or fetishizing them?

Sex educators Jaxson 'J.B.' Benjamin and Hilary Wermers specialize on the intersections of sexuality and disability. I asked them to share some of their thoughts on this topic:

Read: A Sex Educator Tells Us About Sex Ed for People With Disabilities (and Why We Need It)

1. On the most 101 basic level, how would you explain how ableism impacts sexuality?

Jax: Put very simply, ableism impacts disabled folks' sexuality on two different levels.

Ableist behaviors show up in the media regularly which is very hard to get away from in today's world. Disabled representation in T.V. shows, books, you name it, and stereotypes of perfect bodies affect our self-image. We are depicted as "the other", frequently labeled as "ugly", used in the role of the "bad guy", a character to be looked after or pitied or just not represented at all. It's rare to find a representation of a person with a disability who is deemed sexy or a dynamic character which drastically impacts how people create their self-image.

Hilary: Ableism denies the humanity of disabled individuals and their right to sexual agency and autonomy. Ableism stops us from seeing disabled individuals as full people with desires of our own and the capacity for pleasure.

2. Can you speak to the ways that ableism intersections with people with disabilities being either infantilized or fetishized?

Jax: Ableist representations can enforce the stereotype of the "pitiful" disabled person who needs caring for. This narrative dehumanizes the individual, it is subtly but forcefully conveying that a person who is disabled is not a whole person, they are missing their sexuality.

The person is treated like a child who needs to be looked after and has not developed sexual feelings. This paternalistic view results in people with disabilities being isolated from romantic or intimate relationships and has seen forced or secretive sterilizations and abortions performed on disabled folks as we have been deemed not worthy of procreating.

The flip side to that coin is the fetishization that can be pushed on people with disabilities. Devotees that are only interested in a person's use of assistive tech or mobility aides again dehumanize us. This lust for an object or part of our identity does not view the disabled person as a full, multi-faceted individual. A disabled person's sexual identity includes all of them or however much they would like it to.

Hilary: Ableism tells us that sexuality is not for disabled people (infantilization/desexualization) AND that disabled people are sexual objects (fetishization). Disabled bodies are protected and shielded from sexuality by overanxious caregivers and lack of sexuality education while they are simultaneously the object of secret, often shame-laden, lusts.

Read: 13 Myths About Sex and Disability

3. How can people with disabilities reclaim and own their sexual narratives?

Jax: I think reclaiming sexual narratives will look different for everyone. Some folks may want to explore promiscuity in different forms, whether virtually, physically, or other ways. For some, it may look like developing an intentional practice of self-love and care involving pleasurable self-touch and sensations that may or may not be shared with others.

I highly recommend sourcing experiences from other people with disabilities. Gathering information will provide ideas to ideas to try out and supply the feeling of community. Besides reading from disabled authors, my social media feeds are very disabled-centric, and because I'm a sexologist a lot of the profiles have a sexual element to them. Feeds that connect me to other disabled folks being proudly sexual supply me with possibilities of how to engage with and understand my own sexuality.

Hilary: So many people with disabilities often require more medical care and assistive care than temporarily able-bodied individuals, which often involve nonconsensual touch or very clinical touch. Practicing enthusiastic consent with sexual partners, naming their body parts and having those names honored, and finding ways to experience pleasure in their body can all be powerful ways for individuals with disabilities to own their sexuality.

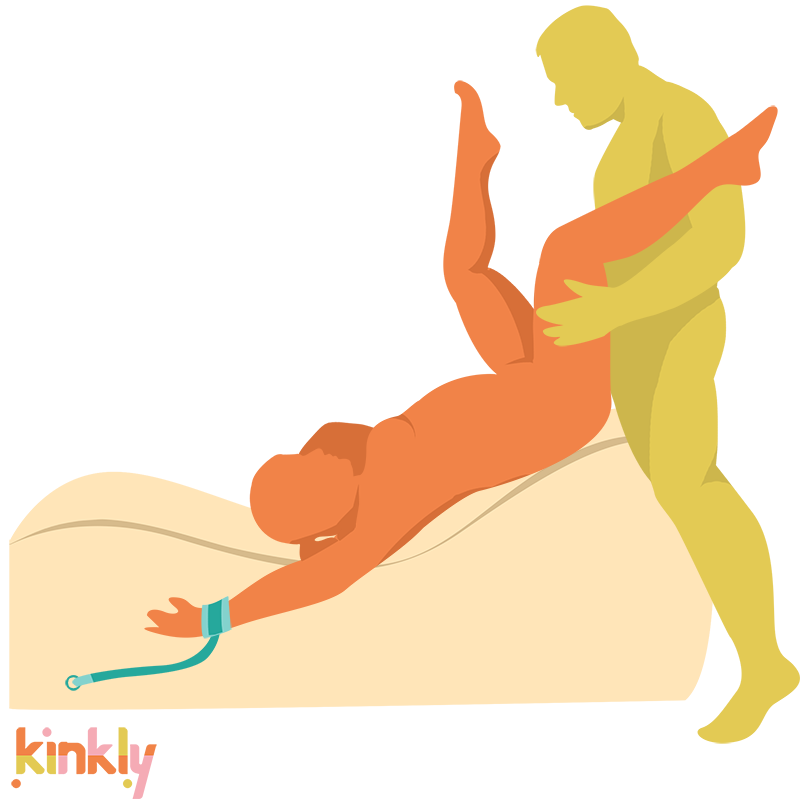

Consensual non-consent (CNC--a previously agreed upon roleplay of nonconsensual behaviors) can also provide space to heal from experiences of nonconsent if it is thoughtfully engaged in.

I also encourage everyone, disabled and temporarily able-bodied, to seek out images of sexy, empowered disabled people. Disabled bodies have for so long been both desexualized and fetishized. It's time to appreciate disability for what it is: an inherent part of the human condition and sexy as hell.

Read: Bondage and Disability: Working WIth Abilities in Play

4. What advice would you give to someone who is temporarily able-bodied but has a partner who isn't?

Jax: My advice for healthy sexual and intimate relationships always comes down to communication. Communicating with yourself to know what you do/don't want, what your boundaries are and how to share that with your partner(s). That includes saying "I don't know" or "Can we pause and pick this up later?"

Figuring out your communication style, or love language, and your partner's is a big part of healthy communicating. Coming to the space with time, patience, and empathy through questions like "Is it okay to ask you about..." or "How does discussing this feel for you?" are great tools to respect boundaries and show care.

Also, do some research! There's not nearly enough, but work on disability and sex is out there (often for free!), as well as, great disabled sex and relationship educators and therapists.

Hilary: For temporarily able-bodied partners of disabled individuals:

- Fully acknowledge your status as temporarily able-bodied. This will give you appreciation and respect for your partner and help break down power imbalances.

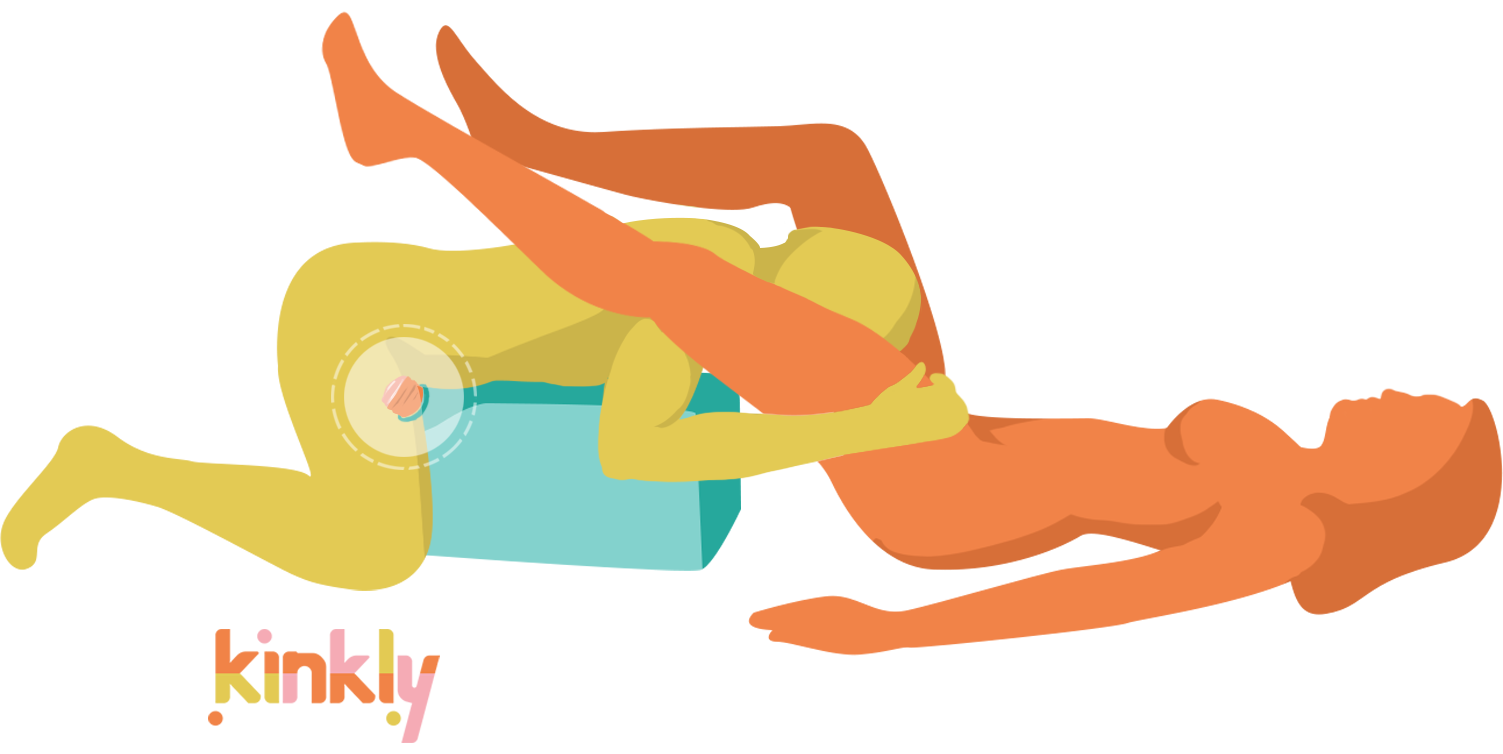

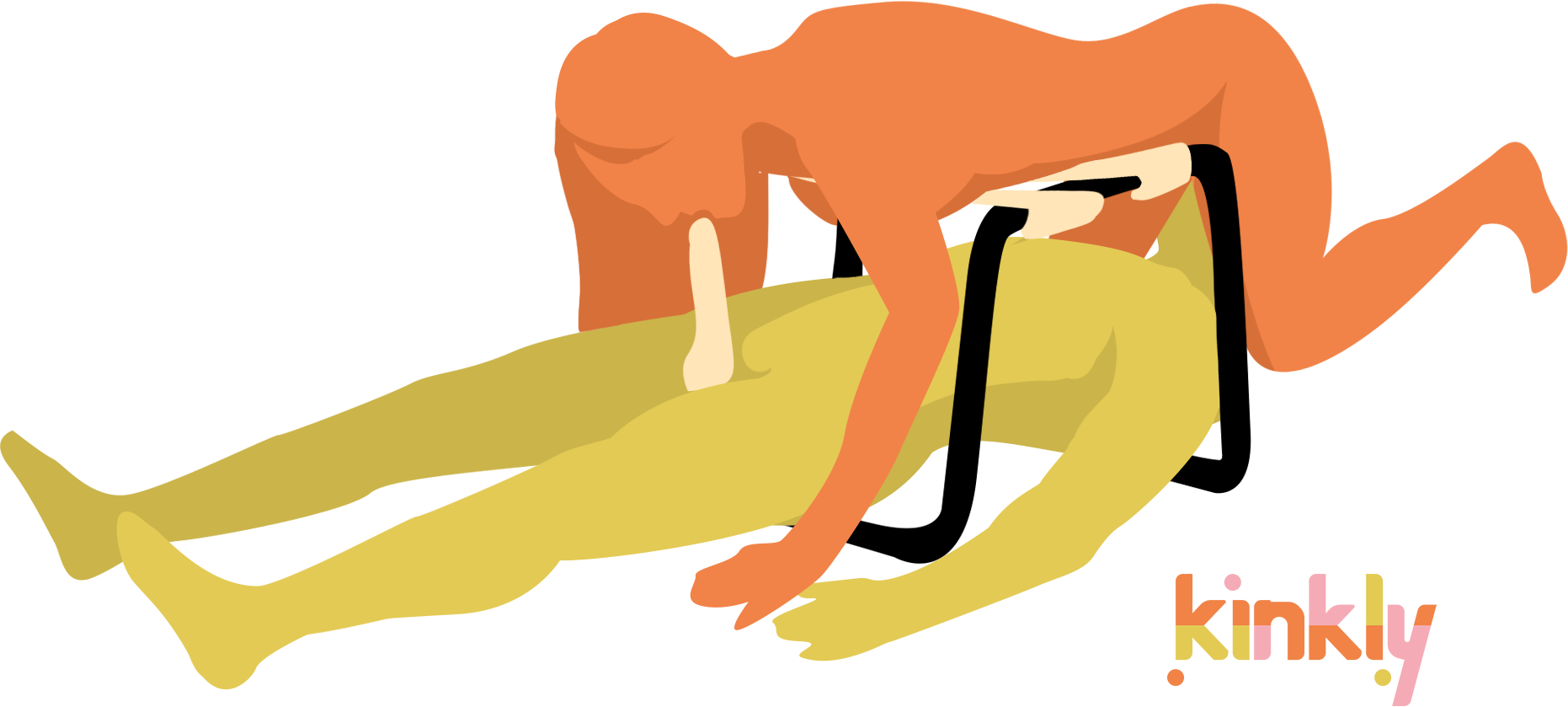

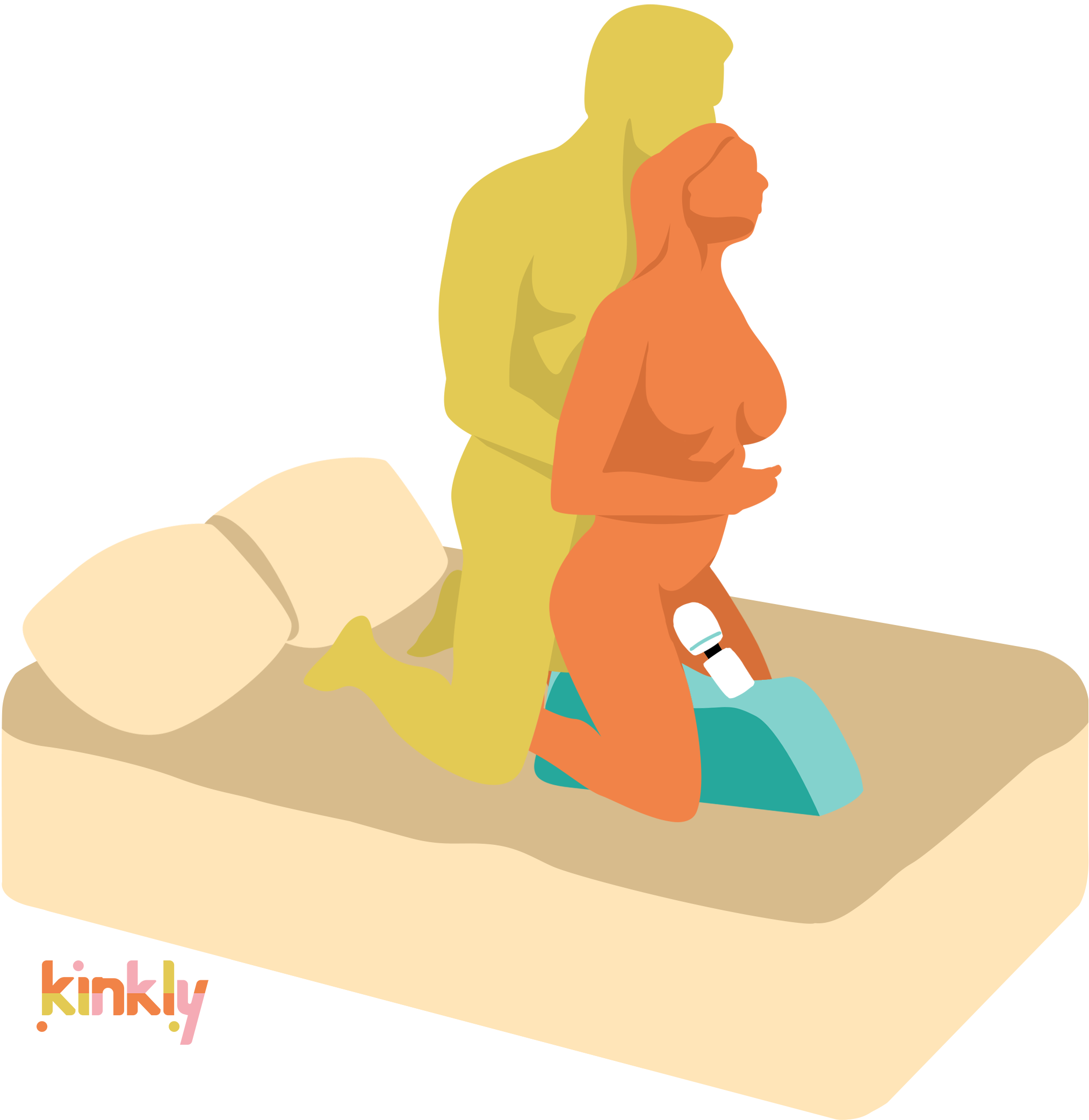

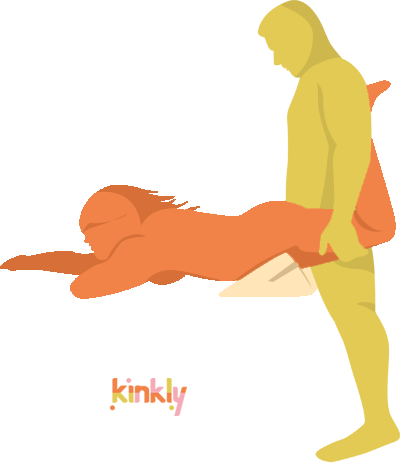

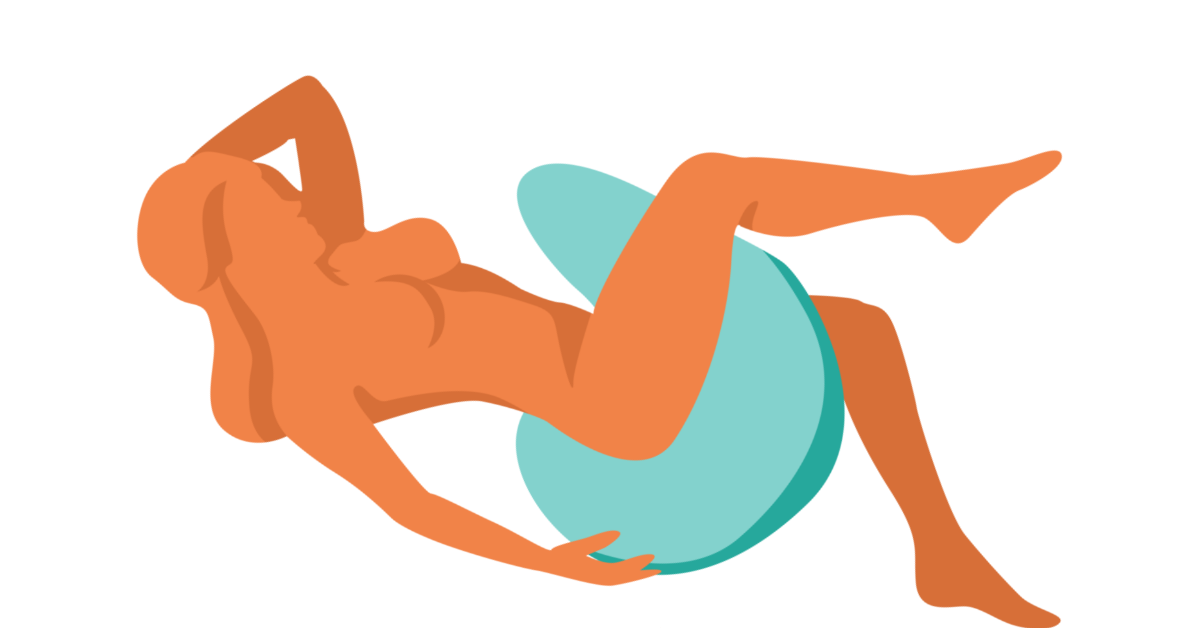

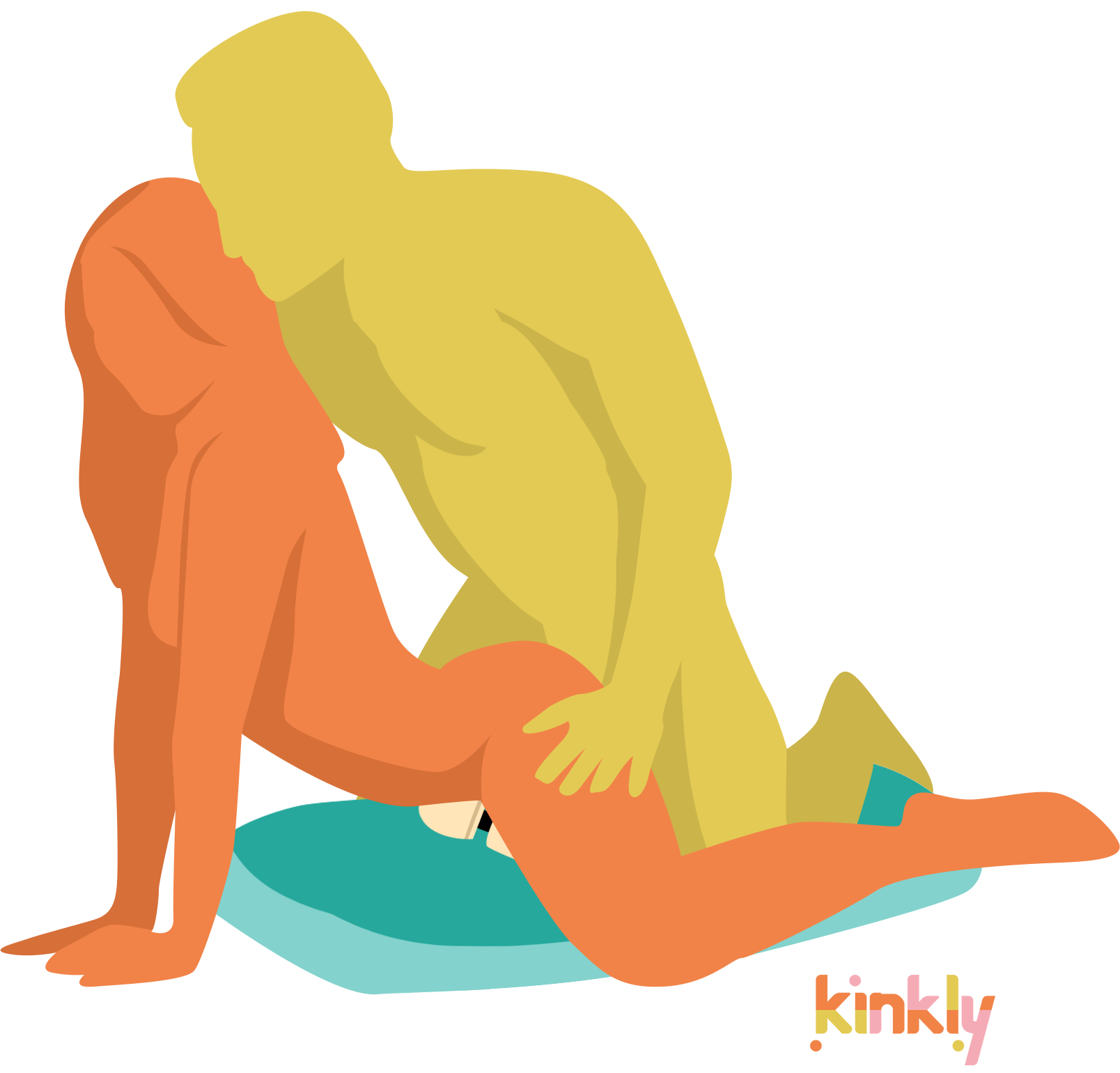

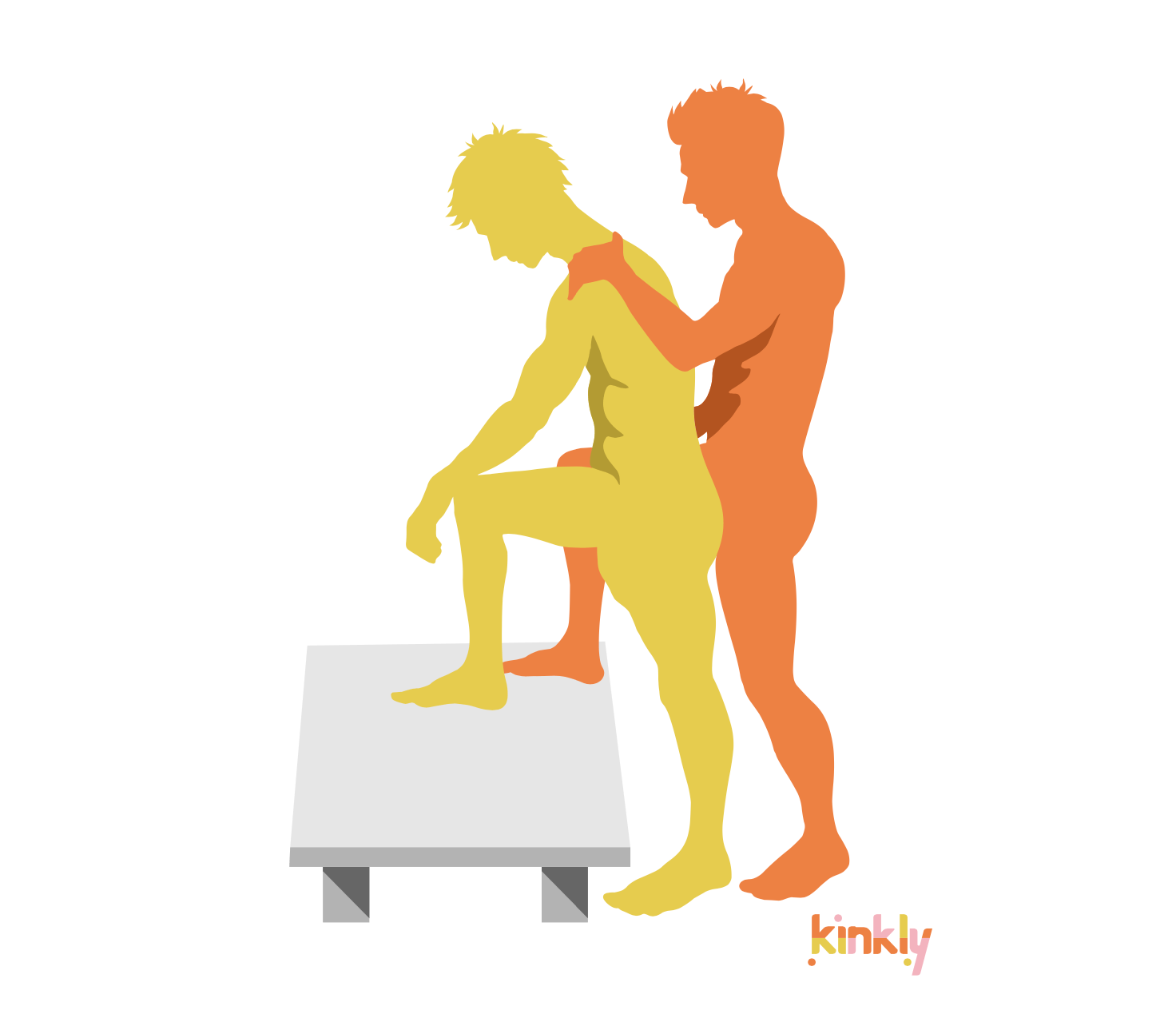

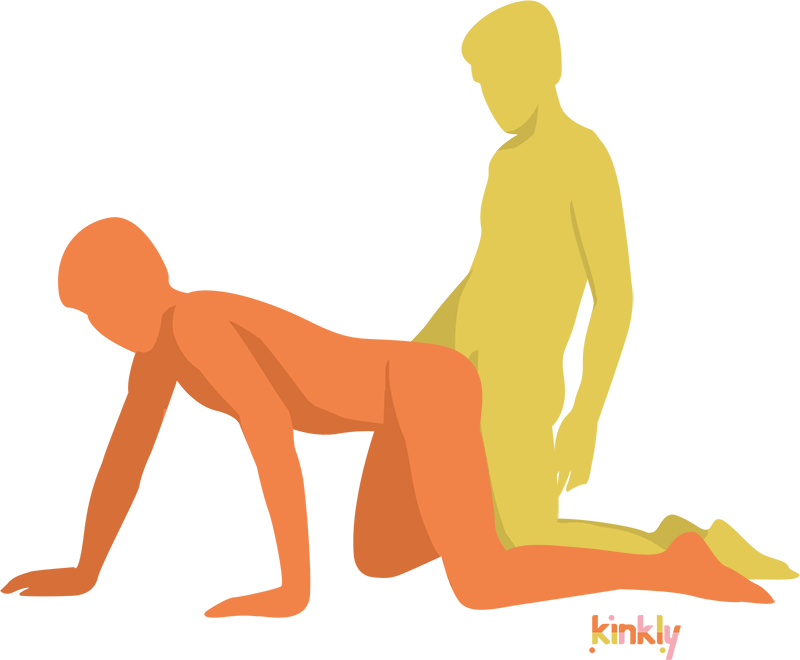

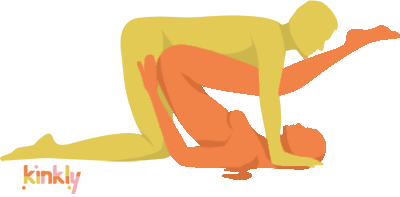

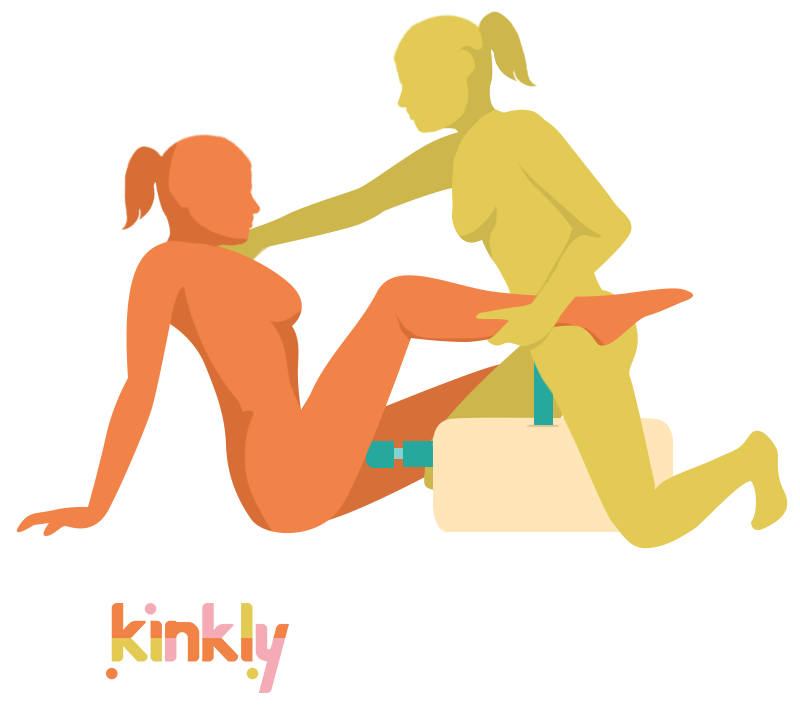

- Your partner is an expert on their body and their abilities. Look to them for answers about what brings them pleasure, what positions and adaptations work for them, what kind of and how much assistance they might need.

- Once your partner has shared a preferred term, a need, or a limit, remember and respect it. Don't make them repeat themselves.